Calculating Return on Capital

A step-by-step guide using Boston Beer (SAM) and Heartland Express (HTLD)

In All Roads Lead to Return on Capital (June 2025), I made the case that return on capital is at the heart of investing. All investments, from a simple savings account to the riskiest startup, share the same common thread.

Let’s take the next step and discuss the process of calculating return on capital using real-world examples. While this post is strictly educational in nature, it just so happens that I made—and continue to make—actual investing decisions using these figures, as I own shares in Boston Beer and Heartland.

Important Note: This is my way of doing it (at the present moment and for these companies). Every analyst has their own preferred method. As we’ll see, there are many departure points where an analyst can decide to alter the basic equation. Above all, aim for consistency.

Example 1: Boston Beer Company

Step 1: Calculate Capital Employed

I like to use capital employed, which starts with assets, as opposed to invested capital, which starts with liabilities and equity. As a short aside, invested capital is simply total equity plus short- and long-term debt capital (including lease liabilities).

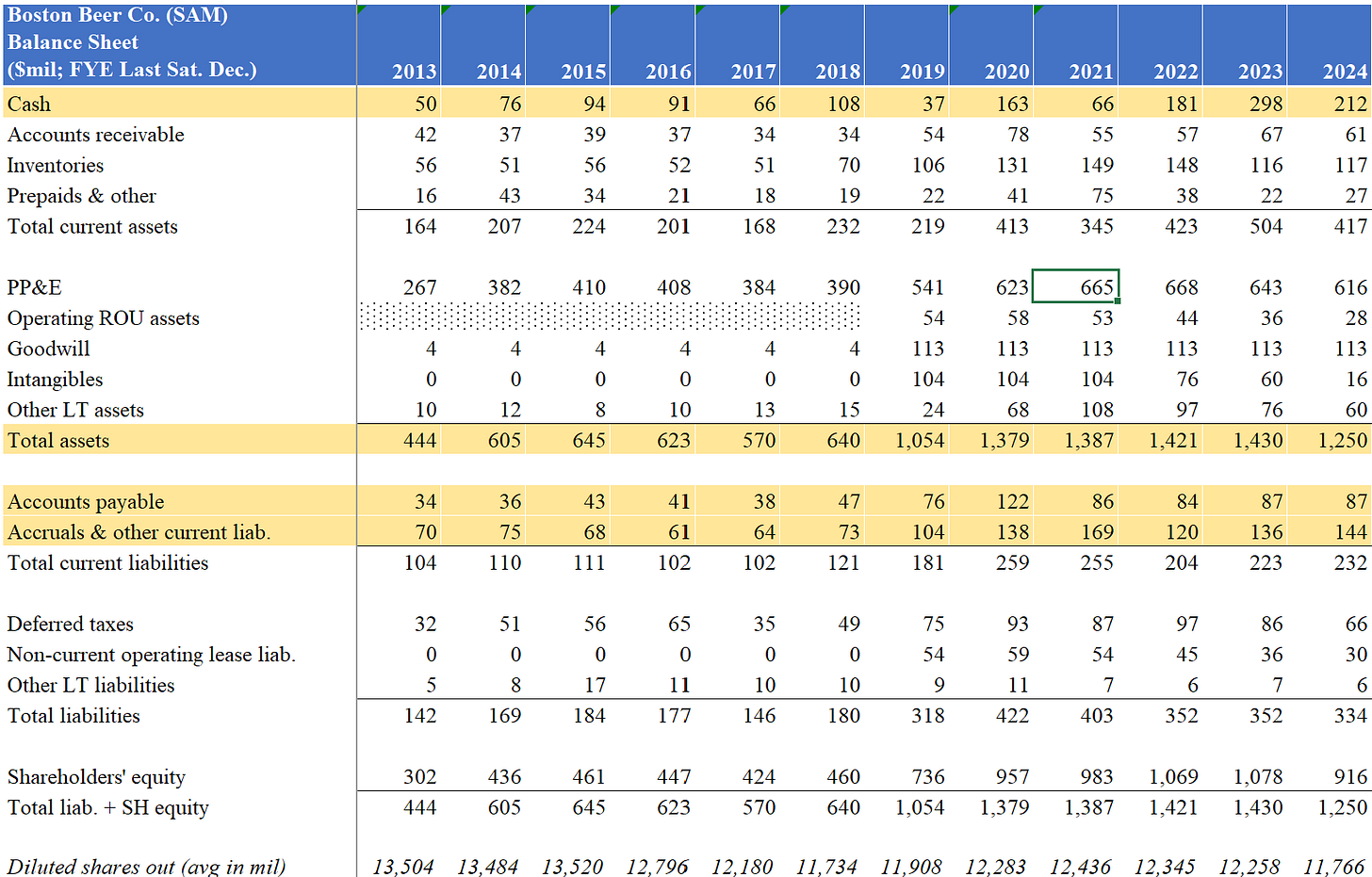

As highlighted below, the relevant accounts here are total assets, cash, and spontaneous current liabilities. Note: The relevant accounts could differ; this is why it’s important to think through the balance sheet carefully and read SEC filings.

Boston Beer Capital Employed

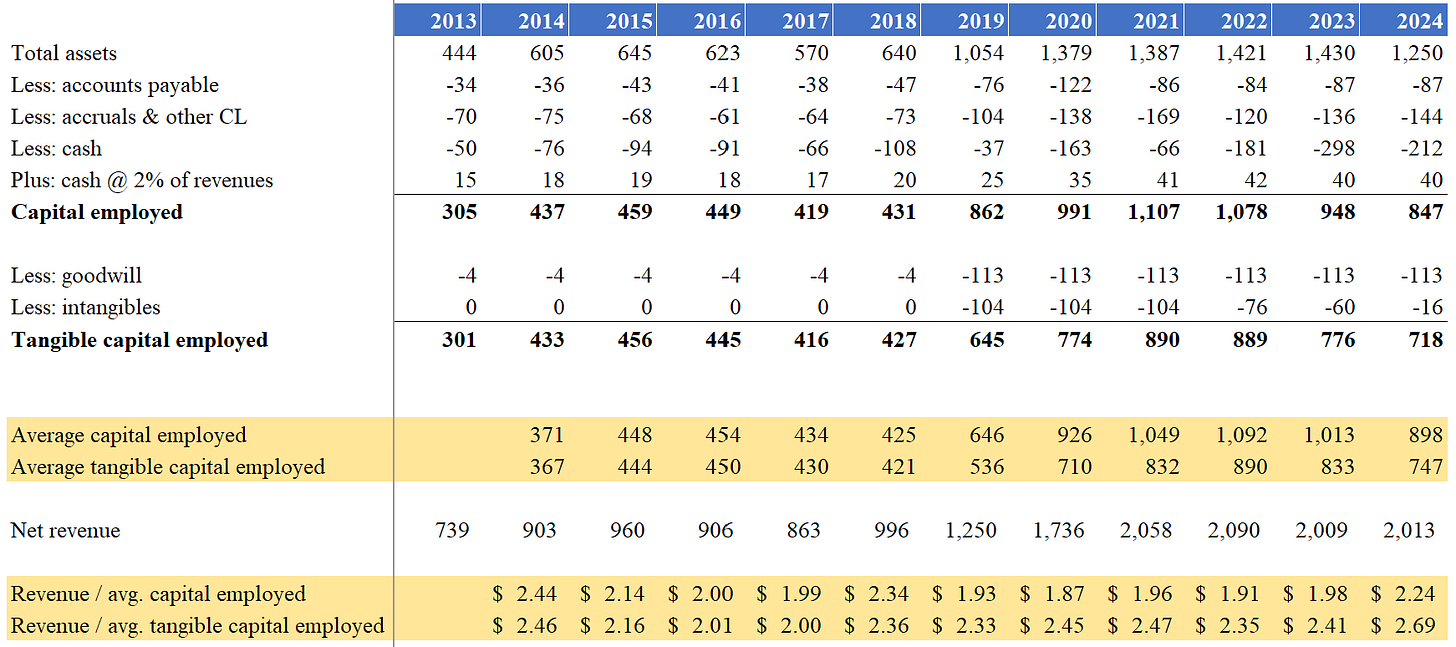

Here’s the calculation (below). Two things to note:

Not all cash is employed in the business; some is excess. You could simply deduct all cash or do what I do and use 2% of revenues as a normalized baseline level of cash that’s needed for everyday business.

Our first departure point: total capital vs tangible capital. Boston Beer has a meaningful amount of goodwill and intangibles on its books. Should this be kept in the formula? Do they represent an asset needed to run the business, one that needs to be maintained just like physical assets? Or should it be deducted, leaving only the truly tangible assets?

I’ve gone back and forth on this point over the years. Buffett talks about tangible capital all the time (here’s a great clip discussing Kraft-Heinz). Michael Mauboussin has a good paper discussing the calculation of invested capital in this paper and appears to favor leaving goodwill/intangibles in.

Another point to consider is write-offs of any kind. Should they be added back to earnings in that year and to capital on an ongoing/running basis? That’s a decision you’ll need to make, too, all informed by research and thinking.

The Extra Step:

I also take a further step of calculating capital turnover, which is simply revenue divided by your preferred capital employed figure. This gives us a way to compare capital intensity to the same company over time and to other companies in the same industry.

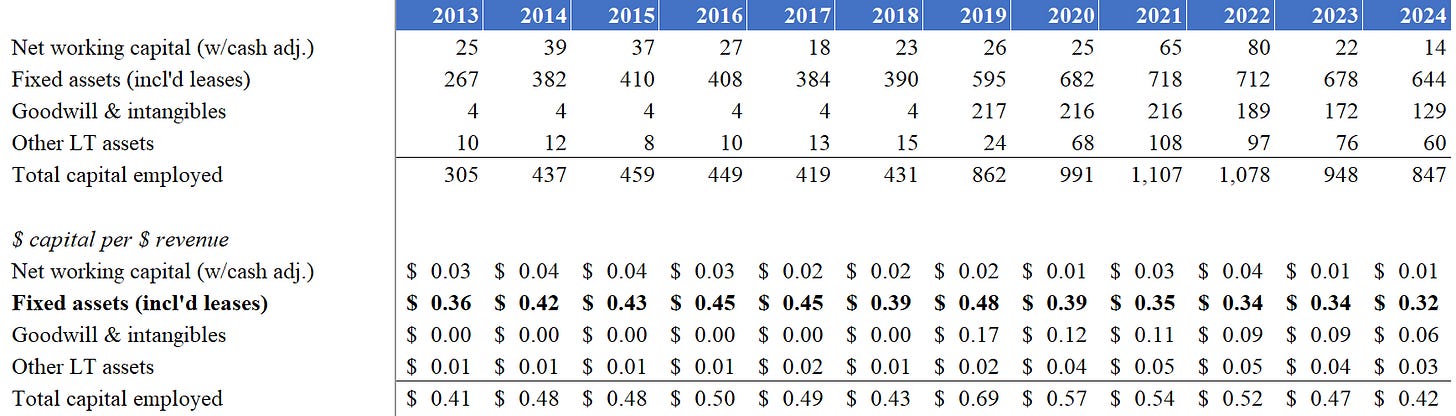

Bonus:

You can go even deeper, disaggregating the capital employed figures (including turnover) into net working capital and fixed assets. It all depends on how deep you want to go. Note for this breakdown, I use capital per dollar of revenue, the inverse of the revenue/capital above. We can see that the bulk of capital employed in Boston Beer’s business is in fixed assets, which makes sense given its business model of brewing beer.

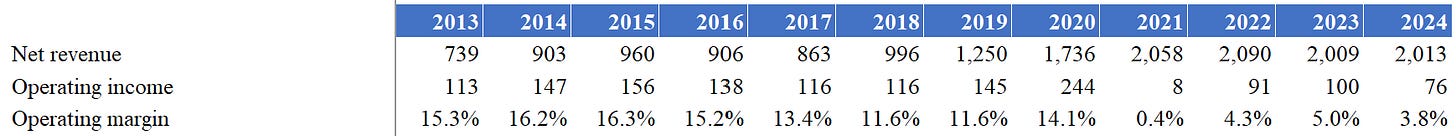

Step 2: Calculate Return or Margin

The first step is deciding whether to use a pre-tax figure or an after-tax figure (EBIT or NOPAT). Either is fine as long as you’re consistent with your capital employed calculation. I like to use pre-tax operating income as a base since it avoids the noise of financing decisions and tax changes. It gets to the core of the operating business quickly.

Here’s what that looks like. Pretty straightforward in most cases. Some analysts add back impairment charges and other one-time items. That may be appropriate in some cases if they’re truly one-time, but the practice is abused.

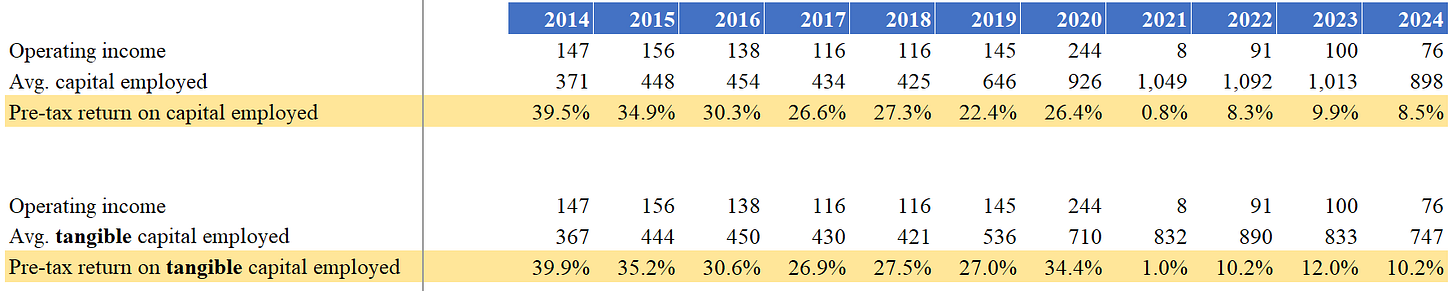

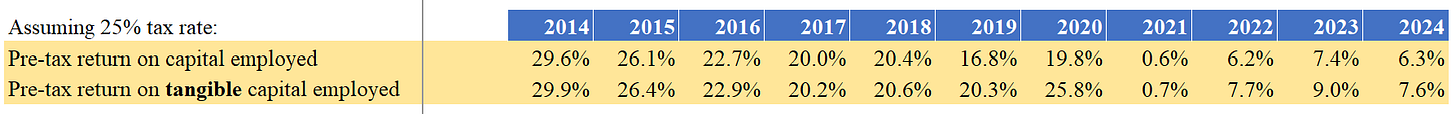

Step 3: Calculate Return on Capital Employed

Let’s put it all together. We can use the direct method of operating income divided by capital or take turnover (revenue / capital) times operating margin (operating income / revenue).

After-tax, it looks like this:

Impact on Valuation

Armed with these figures, you can decide what you’d like to pay for a company. The calculations help you along the way. Say you decide that Boston Beer can earn a normalized pre-tax return on capital of 20% and you demand a 10% first-year return. That’s an easy calculation to make: you can pay twice the underlying capital in the business and earn your return. Growth factors in because you don’t have to pay for future capital employed; your return will “grow up” or approach the underlying returns over time.

What other aspects of the investment process should I explore? Let me know in the comments.

Head over to the dedicated thread to discuss this post with other subscribers.

Example 2: Heartland Express

Heartland uses the same basic calculations applied to a different industry. It also highlights the need to make adjustments to the calculation based on company-specific accounting.

Heartland has two peculiarities you need to understand to properly calculate return on capital: